In Part I of this interview about soil biology with Heather Rinaldi and Nina Folch, we learned some pretty crucial stuff about what constitutes excellent soil, how to recognize when it’s good, and what to do about it when it’s not.

But the one thing we didn’t even mention were earthworms or even vermicompost!

So in Part II of this interview, which will be a little shorter than Part I, I ask Heather and Nina a little about the interrelation of worms and soil, what vermicomposters should know to make vermicompost with biology that really pops under a microscope, how to store vermicompost (if you must), how to reinvigorate lifeless castings, and what mistakes new vermicomposters should avoid.

So without further preamble, here’s Part II with Heather and Nina!

[convertkit form=5120415]

Switching gears to worms

UWC: Let’s talk about soil and earthworms. Does their presence indicate good soil?

I have many readers who are under the impression that adding earthworms directly to soil would rehabilitate it.

Is this true?

Heather: That would be putting the cart before the horse. I would never spend money to add worms to any soil. Here’s why: there are at least 1800 species of earthworms—compost varieties like red wigglers, horizontal burrowers like the invasive worms causing issues in the Northern forests, and deep burrowers that aerate soil. However, any soil devoid of the deep burrowers means that you have issues. Do you use microbe-killing chemical practices? Do you kill your microbes because you till? Do you have bare soil that allows UV light and temperature extremes to kill your microbes? Do you add continuous soil organic matter (SOM) as mulch (or mulch mowing your lawn grass and leaves) to feed your microbes? Improve your practices and attract your worms. They do not come before you set the habitat. Build it, and they will come!

Nina: There’s a real soft spot in my heart for earthworms, but we really need to stop treating them like they’re unicorns in disguise. Worms aren’t magical, and there is a limit to what they can do – especially when “thrown” into an environment they aren’t quite ready to handle.

Composting worms are surface feeders, and not the deep burrowing kind we find deep in our soils. Adding composting worms to your garden soil will likely hurt your pocket more than it will improve your garden. I’m not saying it’s not possible for them to survive. I’m saying it’s unlikely they’ll thrive, and you’re likely to have more losses than wins.

If you want worms in your garden, you want to attract them naturally, and for that you need to take care of other things first. Like Heather points out, they do not come before you set the habitat.

UWC: Does the simple presence of earthworms indicate good soil? Or is it a self-reinforcing cycle?

Heather: If you have no deep burrowing worms in your soil, you have low soil biology. The presence of deep burrowing worms means that you have at least reasonable soil life. If you add worms to lifeless soil devoid of rich organic matter, you have doomed them. Would you put a herd of cattle into a bare pen with no additional fodder and expect them to live? The worms are just part of the soil food web, we need to work to build that entire ecosystem.

Nina: If you are finding earthworms in your garden, especially those deep burying ones, I’d say that’s a good sign. But the real question is, is it the only sign? Absolutely not!

Worms are but one organism in a highly diverse system. We need to stop telling ourselves that all bugs are evil. Ants, beetles, millipedes, centipedes, springtails, spiders, frogs, snakes, and so on. We are so obsessed with killing everything we don’t understand that we end up doing way more damage than good. Nature has a role for these organisms, and unless you stop and learn what that role is – nothing will ever change.

A healthy ecosystem is a balanced ecosystem. “Balance” being the key word here. You don’t get to pick and choose what you like, kill the rest, and then expect to have a beautiful garden. That’s not how nature works, and as stewards of the earth, we really need to support nature, not try and control it.

I can guarantee you that, if your composting bin has nothing but worms and no other bugs to speak of, you’re not making the best compost out there. The same goes for your gardens and fields.

Diversity and balance is always the key.

UWC: What should vermicomposters do to ensure they produce vermicompost that is full of life?

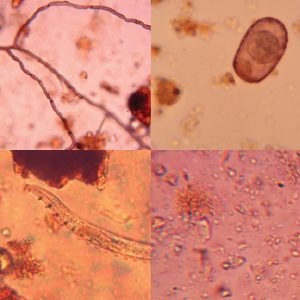

Heather: It isn’t just life, it is a diversity of beneficial life. Most vermicomposters can produce lots of anaerobic bacteria and unwanted ciliates, but it takes a lot of care to make sure you are making something worthwhile for sale or personal use.

Aerobic conditions, appropriate moisture (I call it Goldilocks—not too little or too much, but just right) around 45-50%, diverse bedding and foodstock, including fungi-inoculated material. Make sure your bin is harvested every 3-4 months, so you don’t go anaerobic and lose all carbon soil organic matter. However, you should not see or smell food waste or manure.

And stop worrying about every little bug in your bin. What healthy ecosystem in nature has just one organism? It is all the organisms in the bin, working together, that create a microbe-diverse ecosystem for you. That is what you want to achieve.

Nina: Stop killing everything that’s not a worm. I cringe every time I hear or read comments about people putting diatomaceous earth in their gardens or composting bins because they don’t like ants, or springtails, or mites. Seriously, STOP IT! It’s not helping you, at all, and it’s certainly not helping the planet. If you have too much of something, that’s an indicator that your system is out of balance, and the best solution is to figure out how to bring things back into balance; not nuke the whole bug population around you.

Did you know that the world’s bug population is at a record time low? This is a HUGE problem for life as we know it – including human life. Bugs are food for a vast number of organisms that are now being threatened.

Heather: I have to concur with this. Folks, we need to start understanding and building healthy ecosystems. Those include necessary organisms from apex predators (like wolves and sharks) all the way down to bugs and soil microbes. If you want a livable planet for our species, encourage people to not fear everything else in Nature. If you want your compost, vermicompost and garden to thrive, encourage more life instead of less. I’m shocked by how many people are scared of worms. Worms!

People have become completely out of sync with the natural world.

UWC: I’ve seen heated debates on how long you need to let the worms work before you call a product “vermicompost” or “worm castings.” At the risk of getting hate mail, what is your opinion on the minimum time a bin needs to “work” before producing salable castings?

And if we have to store worm castings, how best should we do that?

Heather: I don’t think time should quantify what you have, however, if you aren’t producing vermicompost that is safe from pathogens AND is microbially dense and diverse, I wouldn’t want it on my personal gardens or lawns. What most people think of as “castings” may be nearly sterile, or worse, full of pathogens. Ours are actually fairly coarse with woody carbon material, but we do our best to check every 65 pounds to make sure we pass our guidelines for excellent microbial inoculants. Some of our Texas Worm Ranch clients are looking at everything under the microscope. They are perfectionists, I can be a perfectionist, and my staff wants to produce the best vermicompost. My team works really hard at it and deserves a lot of credit for continuous improvement to reach high ideals.

Most of our castings are harvested and sold the same week, and we advise customers to use it as soon as possible for best microbe populations. Decreasing moisture can really lower your active biology—and it happens fast. Temperature extremes and low oxygen can impact biology. Ultraviolet light definitely impacts biology. I have large companies that call wanting to rebag our vermicompost and sell as castings under their brand. They want to throw it out in their unsheltered compost yard until they bag at their convenience. Of course, they want to pay basement prices, so we don’t sell to them. The worm castings you get in sealed plastic bags is going to be fairly dead and I would never buy it.

I have customers say, “but I can get a bag at half the cost of yours at (insert big box store).”

A big bag of nothing isn’t a value.

Nina: I think a lot has to do with your inputs. What kinds of waste materials are going into your bins? Are you using manures that may carry nasty diseases? Or are you just adding yard waste? We really need to consider this when making a call on “how long”.

Most experienced professional vermicomposters suggest 120 days of composting, if pathogens are a concern. Some have argued that 60 days might be enough. Who’s to know without proper testing, right? There are a lot of assumptions made in the world of vermicomposting, and little data to support some of these arguments. My best suggestion for businesses, is to test your compost for the presence of fecal coliform bacteria. You don’t need to test every batch, just enough to get an idea of how your system is working (because not all systems are the same!).

If you want to be safe, and you don’t want to spend the money on testing, keep composting to 120 days, and use as soon possible after harvesting – for all the reasons Heather mentioned above. Storing castings is not ideal in any situation, but if you MUST do it, make sure to keep it in the shade and maintain humidity at around 45-50% at all times.

UWC: What are the inputs required for a fungal vermicompost? Are there any other conditions to be maintained (humidity, temperature, etc) to promote fungal growth?

Nina: Fungi use carbon as sources of energy (carbon is converted into carbohydrates, which are basically sugars). They also need a source of nitrogen to build proteins and other essential components.

Most fungal species prefer warm and humid environments – a huge benefit here for vermicomposters, because the requirements are often not too dissimilar to the environment most composting worms prefer.

UWC: The creation of compost tea typically uses a “tea bag” of some sort suspended in the aerated water. Can any fungal qualities of vermicompost pass through the membranes into the tea?

Nina: Yes. I believe 400 micron mesh bags are ideal. This size mesh will allow for the largest of microorganisms (fungi, nematodes, and protozoa) to pass through with ease, and without being damaged, while keeping most of the organic matter inside the bag.

I have seen people use just about anything to brew with (from panty-hose stockings to muslin bags), but these aren’t efficient at all. Some microorganisms are simply too large to pass through these fabrics.

UWC: Is there any real reason why a tea bag must be used to create worm tea?

Nina: Yes. Some sprayers, especially backpack sprayers, are notorious for clogging. The larger, newer models (a lot of landscaping companies use) are usually better designed to handle large soil particles and are much more forgiving when it comes to clogging.

The actual brewer design may also determine whether a bag is useful or even necessary. Some brewers may also have dead spots (areas that recieve little aeration) that often occur toward the bottom of the brewing container, where heavy soil particles fall and go anaerobic. These meshed tea bags help to keep things suspended, and also makes for easy removing (I like to remove the compost teabag after 8 to 12 hours of brewing).

Heather: If the brewer needs it, it’s a good idea to use a bag to keep the material from clogging up an expensive brewer or becoming anaerobic on the bottom of a tank. I have had bags split and had to do the old “blow air up the hose” trick. I don’t recommend it!

UWC: In the vermicompost community we wrestle with whether we should screen our vermicompost in order to produce fine worm castings? Can you guys each take a stab at why you might not want to screen or reasons that you DO want to screen?

Heather: It is a conundrum! If you overscreen, you lose or break up some fungal hyphae. If you don’t screen, you lose a ton of worms and cocoons. If you are just a home vermicomposter, with one or two bins, use the light method of harvesting and get as much fungal hyphae as possible. We are too large to feasibly do that.

Nina: Biology assessments at the lab seem to point to the idea that sifting can be detrimental to microorganisms. So, yeah, there’s a bit of a tradeoff, like Heather points out. I think the key is moderation. Sifting has a somewhat similar effect to tilling as it slices and dices the microorganisms). Keeping sifting to a minimum, whenever possible, is certainly ideal.

UWC: Let’s say you have a newbie looking to get into vermicomposting for the first time. Can you list out some common misconceptions about the process that will steer people away from trouble?

Heather: The best advice I can give is to mimic nature as much as possible. Use the waste you have. There’s no need to buy things like peat or coir. Set up your bin ecosystem as close to a forest ecosystem as you can.

Another key tip is that any system that has water running out the bottom is too wet, and will be anaerobic. I am not a fan of the “nozzle” letting leachate out of the bottom of some designs.

Choose a breathable system like the Urban Worm Bag (shameless plug for you there, Steve!) that will have as much capacity as possible to keep conditions aerobic.

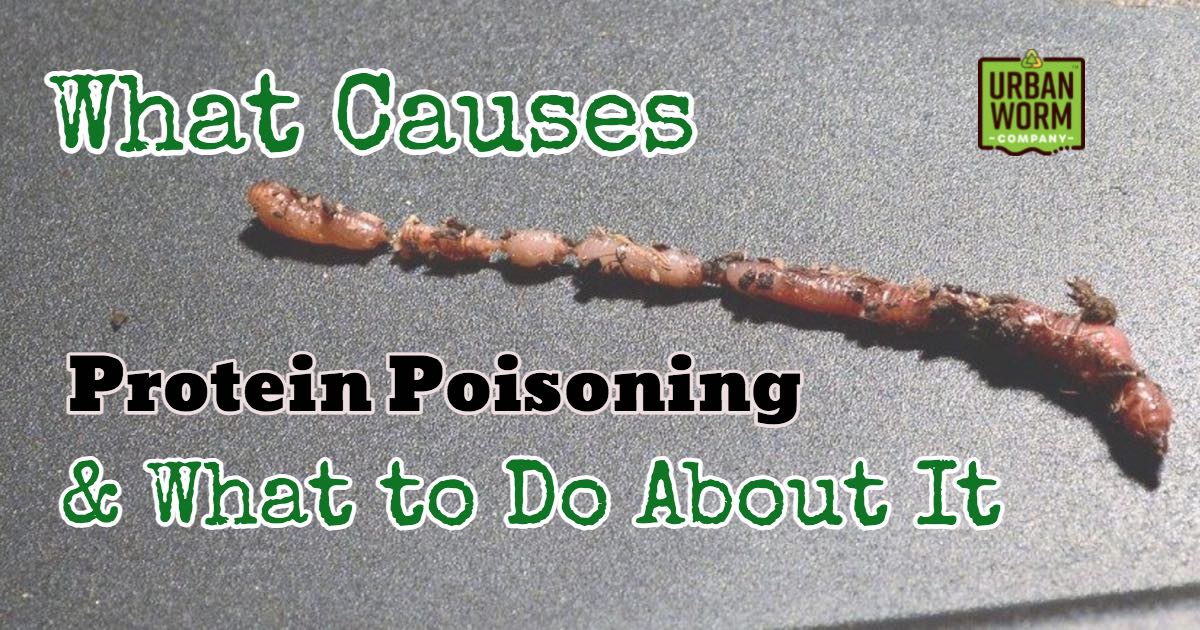

Over-feeding is usually a newbie’s biggest mistake. Not only can it heat up the bin or cause off-gassing that can kill the worms, it also can create anaerobic conditions that set things up for high bacteria and possibly pathogen-promoting conditions. A handful of food every 3-4 days is probably enough for ½-1 lb of worms.

UWC: What is the level of familiarity with worm castings and their benefits within the Soil Food Web community? Is it where you want it to be?

Nina: Worm castings have the innate benefit of providing plants with useful plant growth hormones, even when devoid of life. But castings that don’t contain diversity of life, will not be able to provide your plants with the increased benefits that that life provides – because plants cannot access most of the nutrients found in soil without the aid of biology. Even bacteria alone cannot do this. It is the predators (the nematodes and the protozoa) that finish the cycle that bacteria started. You need the whole food web to be working together.

If you want to learn more about how this works, and how to improve the quality and value of your vermicompost, you MUST come join us at the Vermicomposting Clinic in January. Seriously, what are you waiting for?

Heather: Soil Foodweb consultants understand the possible value of vermicompost, and now is the time for vermicomposters to understand how to achieve what this clientele wants and are willing to pay for!

Personally, I want to help our fellow vermicomposters understand how to maximize the potential value of their own vermicompost, whether they use it on their property or want to have a premium product to sell. To achieve this, it isn’t just spouting “this is good.” It is being able to show and explain to clients why it is good (after you have made it that way) as they look at a microscope sample with you or see 3rd party lab results.

Honestly, you need to be able to prove that with each and every batch. If you can’t look under the microscope and identify what you are seeing and how to analyze the relative quantity, you just don’t know what you have.

UWC: Here’s where I ask you to toot your own horns about your own vermicompost! What makes it awesome?

Nina: Biodiversity! I mean, what else is there to say? We don’t just make worm poop, we make living compost! If you want more than just growth hormones, you need microbial life in your compost.

Heather: Amen, Nina! Through Soil Foodweb training, we know that “good” composts have one fungal hyphae and one amoeba or flagellate in 5 views, 1 nematode per slide, and many species of bacteria. Did I mention I might be a perfectionist? I’m disappointed if that is what we see, because I feel that is a “B” or “C” compost. I’m going for an A each and every sample. We know our soils are depleted of fungi, so we really try to maximize our fungal hyphae. Our whole team strives to make each step of the vermicomposting process an ideal environment for microbial density and diversity. I’m lucky to have smart people that care as much as I do on my team, and we want our clients’ to have success.

Reader Questions

UWC: I asked my e-mail list to send me some questions for you guys and they came up with some really good ones! I wish I could have included them all.

Starting off, my buddy Mary Ann Smith of Valley View Worms near Asheville, NC asked a few good ones.

Firstly, what are the effects of depth on microbial and fungal activity, specifically as it relates to continuous flow through digesters?

Nina: There is no real definitive answer to this question yet. We simply need more data.

I’ve done a few lab analyses that seem to suggest that CFT’s lose microbial populations the further away from the surface, but this may also have a lot to do with harvesting times. Some folks don’t harvest their CFTs for months; some even wait over a year. I have a feeling this is way more detrimental to biology than soil depth.

Some trees can grow roots 20 feet down into the earth – I can’t imagine there’s no biology there! Of course, that root systems is also feeding the biology (via the production of exudates), and that’s something you don’t have in a CFT. How is that biology going to survive and multiply at those depths without access to food? I’m not so sure it can, but, again, we need more data.

Heather: I have two concerns, the first one being oxygen through the system. Can you maintain adequate oxygen through the dense mid-section of the CFT? If so, great. If not, there is a potential for issues.

My second concern deals with the lack of soil organic matter at the end of CFT cycles that have run too long. I haven’t yet seen a scientifically significant number of samples, but what I have seen leads me to question if most CFT operators can maintain good diversity by the time they harvest. I’m NOT saying it can’t be done….it just needs more tweaking and study and retweaking. I love a good science experiment!

UWC: Mary Ann also asked about using mycorrhizal additives. Thumbs up or thumbs down?

Nina: Mycorrhizae spores will serve no purpose in a vermicompost bin, unless you’ve got plants growing in there. The name mycorrhizae is a composite of the Greek words mykos and rhiza, which mean “fungus” and “root”, respectively.

Mycorrhiza needs a living root system that is producing exudates for those spores to even wake up and germinate. If you’re going to add them, do so right before adding that compost to your garden, and not before. And remember, they need to go down into the root system, so make sure to water those treated areas well.

Heather: My opinion is too many people are looking for the magic potion (and to sell magic potions).

Observe and follow nature. What is nature doing?

UWC: Finally from Mary Ann Is it possible to reinvigorate dry/old castings with worm tea (or some other method)?

Heather: If you add foods that have nitrogen, you are probably going to increase your bacteria. If it is liquid, you run the risk of ciliates. This is why we still allow a small reasonable percentage of small, stable carbon OM (small wood or leaf particles) to be part of our VC at Texas Worm Ranch. There is some food, but it is not pathogen promoting nitrogen-based food.

Honestly, I would have some carbon source covering the castings like a layer of wood chips or leaf mould. That would protect and feed appropriate microbes and can be scraped off top when needed.” (Large-scale Australian vermiculture pro) George Mingin concurred with me on both opinions and said he had elevated pathogens with a “high sugar” end feeding. And most compost teas are high in sugar.

Both George and I had reasonable outcomes with storing with high carbon material on top, though you have to maintain reasonable (40-45%) moisture.

Another way to look at adding AACT at end to supposedly “re-activate” VC. If you had a one acre pasture with 10 cows (or millions of microbes in VC) and the cows had grazed down all the pasture, would you add 10 more cows (or millions more microbes) to the pasture to “re-activate” the pasture? That’s ludicrous, right? If those microbes have nothing to eat, they are going to collapse the ecosystem, probably going anaerobic and pathogenic (like the Gulf of Mexico does every year).

UWC: Ron J asked if you guys have any favorite worm tea recipes?

Nina: I don’t! Biology in nature is forever changing – from day to day, and from season to season; why would you want to continually feed your system the same things? Different foods feed different organisms, switch it up guys!! ?

Heather: Billy Schlee makes teas and extracts every day for Preservation Tree Services. It will be a pretty special opportunity to hear him speak and see him making teas and extracts for different plant succession levels. Both Billy and Stephen Haydon (another trainer) have spent significant time working directly with Dr. Elaine Ingham (of Soil FoodWeb). Kim Martin and Laurie Bostic, both of Barking Cat Farm, apply teas to their vegetable farm operations and advise grass-fed beef producers using holistic management on specific teas. Yes, you need to know your soil and your crop and/or ecosystem before coming up with a one-size-fits-all tea.

If you take a soil sample and things look good, you may be wasting money and effort by adding more teas.

UWC: This next one is a really simple, but excellent question. My reader Debbie fully understands how roots “talk to each other” via mychorrhizal fungi and the rest of the environment but wonders how much of that benefit she’s losing by using raised beds. But her bad back much prefers the raised beds and wonders how she can keep some in-ground benefits while saving her back!

Nina: Mycorrhizae is great, but it’s important to realize that most mycorrhizae are species-specific and won’t form an association with most plants. Instead of worrying about mycorrhizae, I’d invest in encouraging other species of fungi. My personal favorite for the garden is the “garden giant” or Stropharia rugosoannulata, also known as “wine cap mushroom.” These are fantastic growers in raised beds. Not only do you get to support your plants, but you also get to eat delicious mushrooms! Can’t beat that!!

Heather: The best thing you can do is to promote a garden ecosystem that will support soil life to help you grow. Do you have plants year-round? Is your soil covered in living plants and mulch? Do you have a diversity of plant families? What beneficial insects are you supporting? Using wood chip walkways in between the beds and having soil contact with the bottom of your beds will be a good start.

UWC: Dawn F asks what is the amount of worms necessary to begin a starter commercial operation?

Heather: Do you want to do vermiculture or vermicompost? My experience is that high-end vermicompost may not be the best medium for growing lots of worms, and vice versa. I would say a ¼ lb of worms per square foot would be a good amount for a beginning vermicompost ecosystem, though I would increase that if you have manures or materials you had pathogen concerns with.

My Takeaways

Firstly, I love these ladies! They are both incredibly helpful members in our community and are my “go to” resource for questions about the parts of vermicomposting that I cannot observe with my own two eyes.

My mild ADHD prevents me from learning in a linear fashion, so I find that I learning in “nuggets,” eventually piecing together a reasonable body of knowledge in my brain. And both Heather and Nina delivered some serious nuggets for me to process. Here are my main takeaways from this interview.

Moisture levels do not always need to be 80-90%

Heather often references the moisture content in her vermicompost hovers at around 50% and when I visited the Texas Worm Ranch a couple of years ago, I was actually struck at how dry it seemed to me. But it wasn’t dry at all, just dry relative to what I have always assumed vermicompost should be! And as I consider the idea of mimicking nature, should we really expect an ecosystem to be 90% moisture throughout? You readers in Seattle may be nodding your heads, but for the most of us, that’s simply not true.

Microbes are the symptom, not the cause, of lively soil

My sales of worm castings are extremely seasonal, almost the point of being binary, as probably 80% of my sales of castings in the Philadelphia area are clustered in the March-May timeframe. But the worms are working year-round, so what do I do to make sure my vermicompost stays lively, especially after I harvest it?

Heather and Nina’s answers really clarified the issue: microbes are life, and life needs to be fed. So attempting to inoculate a dying pile of worm castings with microbe-rich worm tea in an effort to revitalize it is like adding more cows, horses or other grazing animals to a barren pasture and expecting them to bring it back to life. The food that microbes eat has to be present too!

Bugs in your vermicompost are OK. In fact, they may indicate good things!

“This is a worm bin. WTF is that bug doing in here!” is a reasonable response for someone who treats a worm bin like an assembly line rather than an ecosystem (like I did until about a year ago!).

So while ants may indicate dry conditions, our first thought shouldn’t be the brand of ant trap we should buy. Rather, we might ask why they find the bin hospitable in the first place and whether this is a problem to be fixed. For instance, I currently have a heaping layer of dry leaves on top of my worms and it’s not uncommon for me to find ants in the leaves.

But if we’re mimicking nature, wouldn’t it make sense that the top, dry layer of a forest floor would feature ants, but the moist layer of duff underneath would not?

Wrapping It Up

As always, this was a great education for me, and hopefully you too! I always learn so much from these two.

Whoa, Steve! So much GREAT info in these two articles!!! Thanks for pulling it all together for us! And thank you, Heather and Nina, for your willingness to share your expertise!